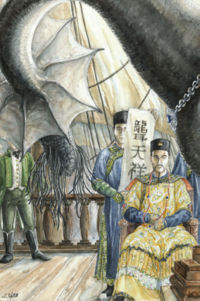

Prince Yongxing

Contents

Character Profile

| Name: | Yongxing |

| Date of Birth: | 1752? died in 1806 |

| Service: | Empire of China |

| Rank: | Prince |

| Nationality: | Chinese |

| Billets: |

Biography

Prince Yongxing was the oldest son of the Jiaqing Emperor. If he had wife and children of his own, nothing was heard of them by William Laurence.

Cultural stance

Yongxing was strongly opposed to allowing Europeans to enter China. His attitude towards Western nations, although perhaps extreme, was not atypical of the Qing government in China. He viewed Britain as a lesser nation, comparable to China's other tributary nations and owing "threefold gratitude and submission to the Emperor."

Yongxing told Laurence that China was sufficient unto itself and did not need Britain's "trinkets, your clockworks and lamps and guns." Yongxing's equation of Christian missionaries with opium smugglers baffled Laurence, who thought that allowing Western merchants into China would bring "the benefits of free and open trade to both parties". However, Laurence may have been unaware of the pervasiveness of the opium trade by the British East India Company.

Yongxing also insisted that companionship with Celestial dragons should be limited to the Chinese imperial family. When the albino Lung Tien Lien was hatched, there was a proposal to send her to a prince in Korea; Yongxing took her as his own companion, even though this ended his own chance of becoming Emperor.

Based on the same moral principle and his anti-Western views, he also opposed sending away the second-born egg of Lung Tien Qian to Napoleon Bonaparte. Even for proponents of this plan, the rank of the "Emperor of France" was less important than simply avoiding the creation of rival claimants to the Chinese throne. Yongxing was unable to prevent the egg from being sent away, but before it could reach Napoleon, it was captured by the British Royal Navy and hatched at sea. The dragonet chose Captain William Laurence as its companion and allowed him to name it Temeraire.

Yongxing's stance was apparently vindicated by the news that the Celestial hatchling had been paired to a "common soldier" to enter active service in the British Aerial Corps, both of which were unthinkable for Celestials in China.

Chinese Embassy

A Chinese Embassy delegation was sent to retrieve Temeraire (whom they named Lung Tien Xiang). Yongxing led the delegation, which also included Liu Bao and Sun Kai. They travelled to Great Britain on four merchant ships belonging to the East India Company. The ships initially demanded payment, but were confiscated by Imperial edict. The ships' crews were incensed, as were other British personnel who learned of it, but the British government was anxious to avoid offending the embassy and tried to keep the confiscations secret.

The embassy attempted to persuade Temeraire to come back to China, but he refused to leave Laurence. When voluntary separation proved impossible, the British government ordered Laurence and his crew of aviators to accompany Temeraire, the British envoy Arthur Hammond, and Yongxing's embassy back to China on the HMS Allegiance.

On the return voyage, Yongxing tried to win Temeraire's trust by teaching him Chinese characters and literature, as well as describing the lifestyle of dragons in China. Temeraire was eager to learn these things, but rejected Yongxing's suggestion that in China, he might have a companion more "worthy" than Laurence.

Since Yongxing could not separate Temeraire from Laurence, he tried to separate Laurence from Temeraire. These attempts included outright commands, cajolery that life in China would be better for Temeraire, and the open offer of 10,000 taels (almost 900 pounds in weight) of silver for Laurence and general trade advantages for Britain. After all of these failed, Yongxing's servant Feng Li twice tried to kill Laurence before being washed overboard in a storm.

Return to China

On reaching China, Yongxing and Lien were affectionately reunited.

Yongxing continued to apply pressure to both Temeraire and Laurence. He brought his youngest brother Prince Miankai for an incognito introduction to Temeraire. (Emily Roland and Peter Dyer had enough Chinese to learn the boy's name and identity while playing with him.) Perhaps knowing that Temeraire would spend the night with Lung Qin Mei, Yongxing may have arranged a hunhun attack on the British delegation to take advantage of Temeraire's absence.

At a theatrical performance in Peking, Roland pointed out Miankai beside his older brother Crown Prince Mianning and their uncle Prince Yongxing. Hammond and George Staunton quickly deduced that Yongxing wanted Temeraire to accept Miankai, then place the boy on the throne as a puppet; Yongxing would then take actual power as Imperial Regent and sever all ties with the West. This gave Yongxing a motive for killing Laurence.

Temeraire heard Hammond and Staunton, which intensified his existing desire to kill Yongxing. As the theatrical performance continued, another attacker disguised himself as an actor and hurled a knife into Laurence's shoulder. Temeraire promptly killed the attacker and turned on Yongxing. In the ensuing duel between Temeraire and Lien, Yongxing was accidentally killed by flying debris.

Aftermath

Prince Miankai confirmed that his late oldest brother had promised him his own Celestial and asked if he would like to be Emperor. Yongxing's supporters were cast into disgrace, leaving Mianning ascendant at the court.

Hammond arranged to have Laurence adopted as a son by the Emperor, a technicality that allowed Temeraire to confirm his choice of companion in the traditional vein. Laurence was also granted an estate in the capital, which would be occupied in his absence by Hammond and the other British diplomats.

Lien, mourning Yongxing deeply, was persuaded by the French ambassador De Guignes to revenge herself on Temeraire and Laurence by travelling to France to assist Napoleon.

Historical context

During this historical period, the British East India Company was smuggling hundreds of tons of opium into China each year. This went on despite the fact that opium had been illegal in China since 1729 and that the Jiaqing Emperor had reaffirmed the opium import ban in 1799.

There was far more demand for Chinese tea, porcelain and silks in Britain than for British goods in China. Britain's trade deficit was compounded by the disparity in monetary policies between Britain's gold standard and China's silver standard. Britain was thus forced to buy silver from other European nations in order to trade to China for goods.

In order to address the British trade deficit, the East India Company pursued an opium monopoly in Bengal. By 1773, they had obtained it. Opium produced in Bengal was sold by the Company to various agents and traffickers in Calcutta with the understanding that it would end up in China. The proceeds from illegal sales of opium in China were then paid into the Company's factory at Canton, where they were used to purchase tea and other Chinese goods.

To understand Yongxing's attitude towards Britain, one need only imagine what would happen if a small 21st century nation attempted to balance its trade deficit with a larger and more powerful one - the United States, for example - by smuggling heroin or cocaine into the larger nation.

Deviations from History

Historically, Yongxing (Prince Cheng; 1752-1823) was the eleventh son of the Qianlong Emperor. Known as "learned and intelligent", Yongxing served in the military council and treasury of his older brother, the Jiaqing Emperor, but was removed from those positions in 1799. Afterward, Yongxing went into seclusion and became a noted calligrapher, but is said to have died deranged and impoverished. His mansion was eventually inherited by his great-grandson.

References

The Vicissitudes of Prince Chun's Mansion : sections "The Villa of Mingju" and "Transforming a Mansion into a Princely Residence".

Rhoads, Edward JM. Manchus & Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861-1928, p78. University of Washington Press. 2001.